One of the things I did not expect to get out of the recent Check Point Experience conference was: a book to read. That’s exactly what happened when, due to an encounter with Flash Foresight author Daniel Burrus on Twitter, a book showed up on my doorstep.

The Twitter encounter happened because Daniel Burrus spoke at Check Point Experience and I tweeted a few photos from his talk. Though he had about a half an hour slot, I could have listened to him for hours. Many of his insights could easily apply to the field of information security. In fact, plenty of the trends he discusses have immediate implications to the field.

Depending on how quick you read, you may be able to knock it out in an evening or two. This book is definitely a recommended read. Unlike many “business” books I’ve read, this was an easy read and found it to immediately resonate with my own experiences. I also found it to be very optimistic. Specifically, the problems we have today will be solved. The question is, by whom and how? If you apply some of the principles of Flash Foresight, maybe it could be you?

Walking Through the Seven Flash Foresight Principles

Daniel Burrus breaks down the process of Flash Foresight into seven principles. The application of one or more of these principles can be used to solve a variety of challenges. Surely, they can help us in infosec, no?

The first place to start: certainty. Specifically, what you know. That is largely reflected by trends:

The main difference between hard trends and soft trends is: level of certainty in the trend. They can sometimes be hard to tell apart, and people often make poor decisions because they can’t tell the difference.

A soft trend are “future maybes.” They can be changed. For example, your organization’s information security budget. The time it takes you to respond to the inevitable breach. You do have a response plan, right?

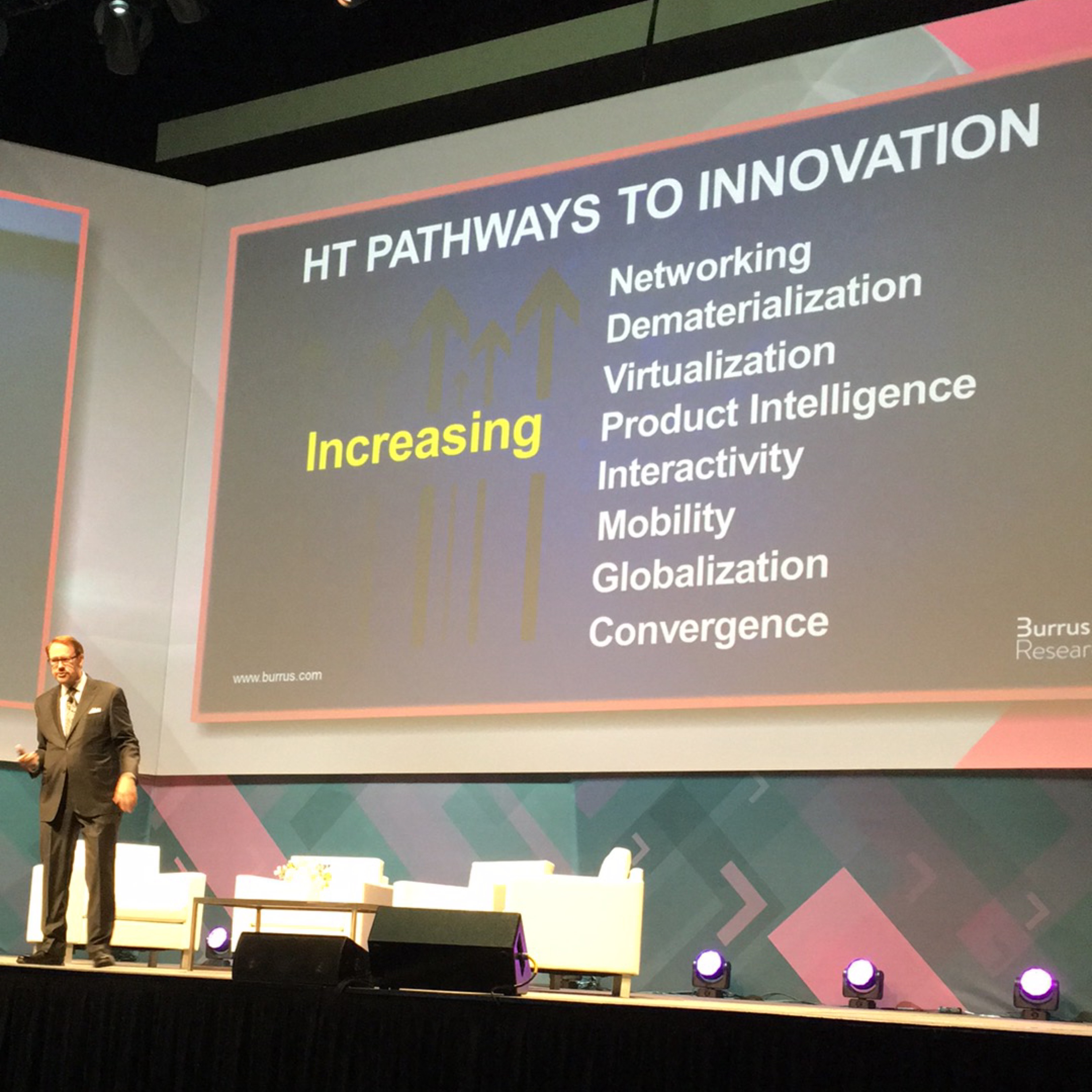

A hard trend cannot easily be changed. For example, the level of technological innovation, particularly in three key areas: processing power, storage, and bandwidth. The trends point to an ever increasing quantity of all three at ever decreasing costs.

Think that doesn’t have implications in information security? You bet it does, and I bet you’re already seeing it: more business information on more devices from more places in the world. The problems will only get worse.

It’s far easier to see the future when you start with what you know. If you look at the hard trends and know where innovation is taking us, it’s pretty easy to anticipate the future (the second principle).

As some of you probably know, I spent 10 years working for Nokia, which was, in those days, the largest mobile phone manufacturer in the world. They were also in the network security business, which is where I worked. That said, I was exposed to many of the mobile phones Nokia made and thus I saw these Pathways to Innovation play themselves out from a vantage point somewhat different from a typical consumer:

It was very obvious to me in the 2000s that smartphones would become our personal computing devices–personal computing devices that accessed websites and had data on them. Nokia, being in the handset business, the network infrastructure business, as well as the security business, was uniquely positioned to provide this security both on the handsets and within the network.

It was one of the many opportunities that Nokia did not have the foresight to take advantage of. Nokia, as mighty as it once was in the smartphone industry, lost out and lost big. Had they made a proper transformation from the inside out (the third principle) as they had done several times throughout their 152 year history, they might still be a household name. Instead, since they transformed largely as a result of external forces and trends, they are barely a blip on the radar.

Another thing Nokia failed to do: take their biggest problem and skip it (the fourth principle). At the time, one of their biggest challenges as far as breaking into the US market: working with the US mobile operators. They wanted nothing to do with Nokia’s products. Meanwhile, they could have easily marketed and sold the products to the US public directly, bypassing the operators.

To bring this back to information security for a moment, what is our biggest problem in information security? Surely it has to be all that data on all those devices connecting from everywhere with data hosted everywhere using our traditional information security tools. What if we could skip that problem and bake security into the data and/or the method used to access that data?

Sometimes, the solutions to your problems are also in the opposite direction everyone else is looking (the fifth principle). For example, I see a lot of newer security vendors focusing on detection of threats rather than prevention of threats. While I’ve said a few times this is not an either/or proposition, I openly wonder: as infrastructures grow more complex and more virtualized, all driven by hard trends, how helpful is detection by itself going to be in the long run? Unless it is followed by automatic remediation—or better, preventing the incident in the first place—it will be just one more signal that gets ignored.

Information security has no choice but to redefine and reinvent how and what it does (the sixth principle). The underlying infrastructure that supports our business is commoditizing and evolving rapidly at a rate that will only accelerate. Likewise, security vendors will have to find a way to continue to provide unique value in this environment else their products will be replaced.

Finally, the future is largely what we envision it to be (the seventh principle). Do we envision a future where the threats run rampant over our networks or do we envision remaining one step ahead and keeping the threats at bay (or at least contained)? You may need other resources to achieve it, but it starts with a clear future vision. To shape the future will require communication, collaboration, and trust—all something information security is in the critical path to ensure happens.

This diagram in the book I think illustrates something that I already lived:

I’ll ask those of you who used my FireWall-1 FAQ back in the day: what did that content represent to you? Data? Information? Knowledge? Wisdom? I’ll settle for knowledge since what I had there was largely product specific. Wisdom is probably stretching it.

But is it? I’ve had numerous people come up to me over the years thanking me for that FAQ as it helped them become information security professionals. Back in the 1990s, there wasn’t a whole lot of information out there. Rather than keep it locked up, I shared it with the Internet. I collaborated with people on the Internet to improve it. And, because the information was largely accurate, and I was accountable for mistakes, people ultimately trusted it.

Even though I haven’t operated that FAQ site in more than 10 years, I built a very nice career for myself as a result. Maybe if the information security industry would communicate better, truly collaborated with each other, and operated in a truly trustworthy matter, we could all be one step ahead.