As much as we might want to see different authentication methods available, passwords aren’t going anyway anytime soon. This means a significant part of our security online comes down to choosing good passwords.

There are three basic rules for choosing good passwords:

- The more complex the better

- The longer the better

- Don’t use the same password on multiple sites

Some services like Office 365 are being criticized for only allowing 16 character passwords. Some services offer even less than this.

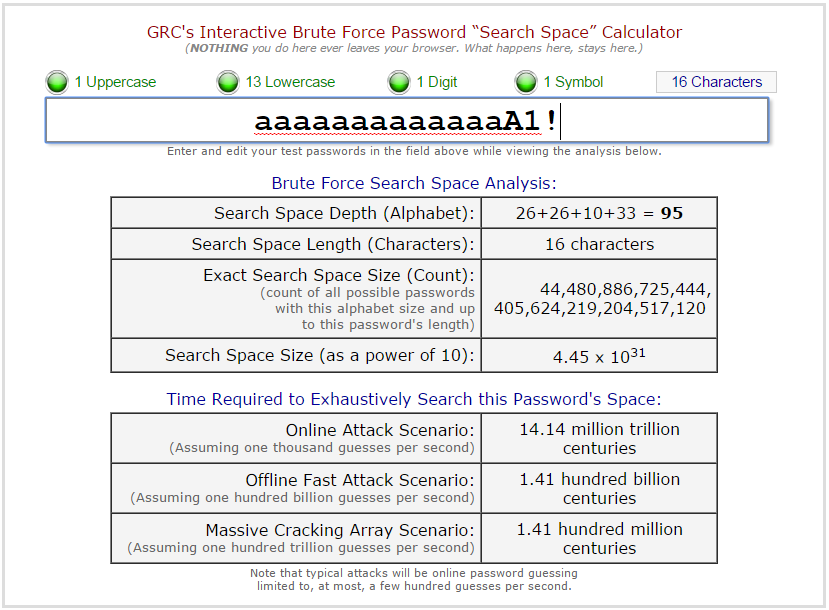

If you actually do a little math, and choose the characters in your password carefully enough, perhaps using a tool like LastPass to generate and manage the passwords, even a 16 character password is more than strong enough to withstand a brute force attack!

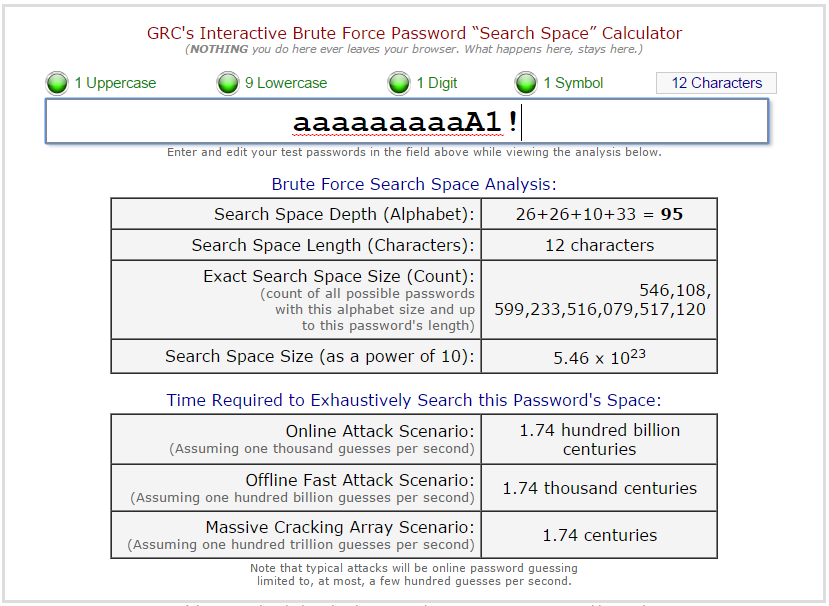

To demonstrate that, I’m going to use the GRC Haystacks tool just to show the search space required in order to find a given password. Yes, I know there are some in the security community that poo-poo some of the contributions to information security that Steve Gibson has made. The tool is merely expressing the results of math and is being used for illustrative purposes.

A password can theoretically have four different types of characters:

- Uppercase characters (26 possible options)

- Lowercase characters (26 possible options)

- Numbers (10 possible options)

- Special characters (33 characters)

This gives us a total of 95 possible values for a given character of a password. Note that this may vary from site to site as some sites might restrict the special character space. Some sites might even allow for emoji, which I am excluding since outside of smartphone platforms, these are not universally available.

Let’s assume we pick a 16 character password that leverages all four character types and is relatively random. The time required to exhaustively search this space with a tool like hashcat or John The Ripper? A much longer time than I can even conceive of!

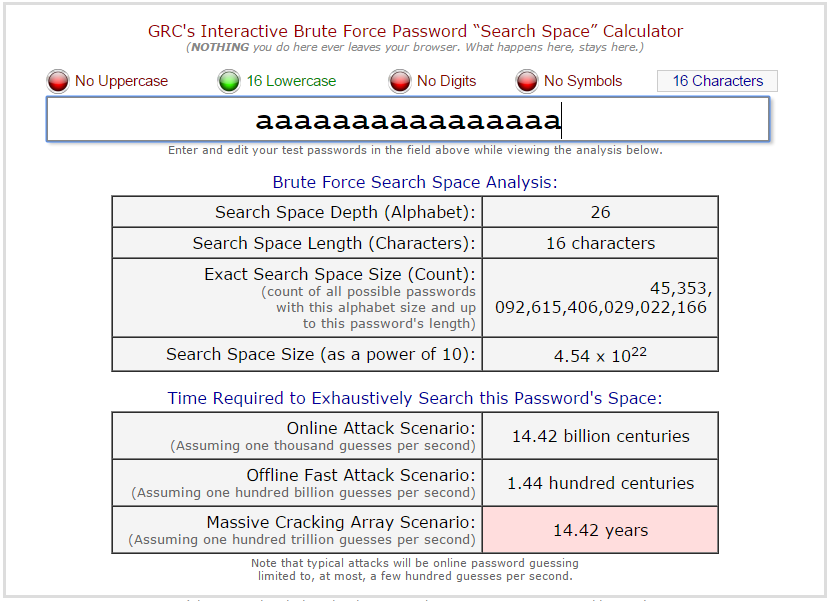

What about if I choose a 16 character password that is all lowercase, but random? Even if a lot of computing power is thrown at the password hash, we’re still looking at several years of computing time:

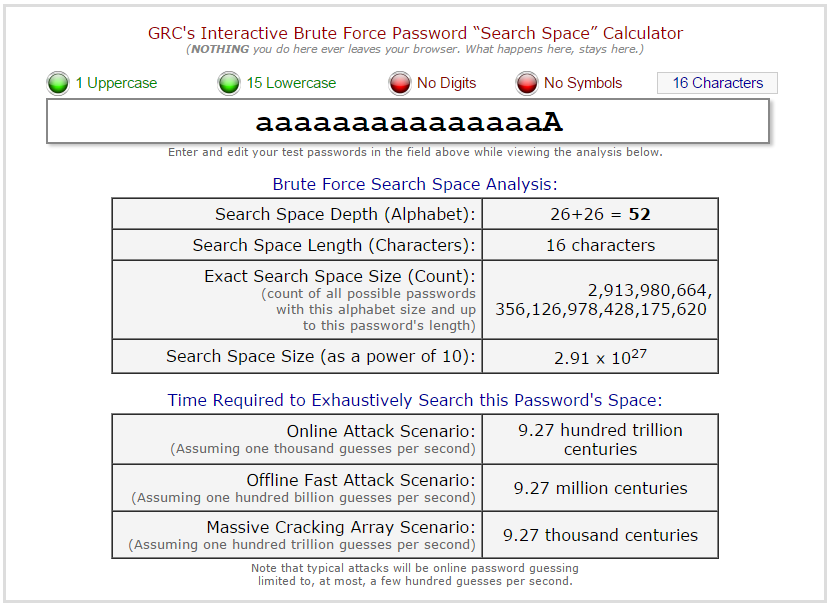

However, by adding a little bit of complexity, say, uppercase characters, the search space suddenly increases by orders of magnitude!

Even a 12 character complex password has a pretty large search space to search through:

All of this assumes you are choosing truly random characters for your password. If you’re using a well-known password manager, it’s probably random enough. Obviously, if you choose dictionary words for your password, or simple variations thereof, the odds of someone guessing your 16 character password are much higher.

Then again, how might someone perform a brute force attack on your password? Certainly if someone leaks the hashed passwords it’s possible. It’s likely not the result of an online brute force attack as that is likely to be detected and/or blocked and will most certainly take much longer.

And yes, the amount of time it takes to validate a password is a factor here. To illustrate this, let’s talk passcodes on phones. At least on Apple devices, if you enable the wipe feature, Apple will wipe the device after 10 failed passcode attempts. The phone only allows passcode entry via the screen and each attempt takes 80 milliseconds to process, as I discussed previously. After a few failed attempts, the phone will lock out additional attempts for a period of time. Which means, it’s not like someone can pick up your phone and a few seconds later, your phone is wiped.

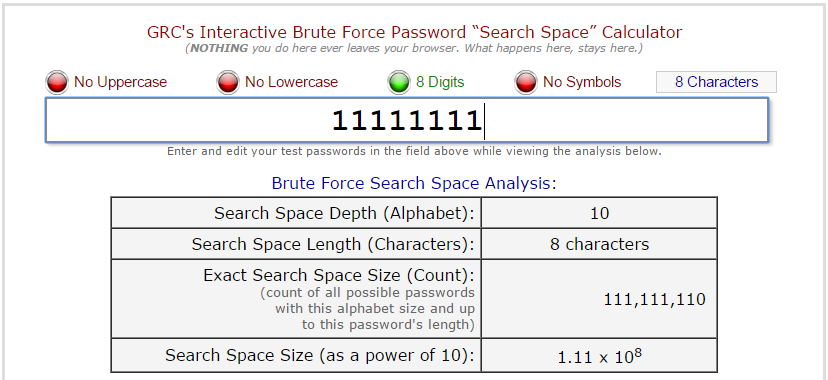

With those constraints in place, how long and complex of a passcode do you really need to keep yours phone from being unlocked by someone other than you? Probably nowhere near as many as you think, so long as you avoid obvious and common ones. For the sake of argument, let’s look at an 8 digit passcode:

To exhaustively search this space, assuming 80ms per guess and no other limiting factors, it would take about 103 days to try all possible combinations. Since there are other limiting factors as noted above, including the fact that the ability to automate passcode guessing is limited, it would take a bit longer. Of course, if the iPhone owner enabled the “erase after 10 failed attempts” option, all bets are off.

The bottom is line is, when you actually look at the math, you don’t need quite as long of a password as you think you do. Assuming the limit is at least 12 characters and all special characters are supported, you can make a complex enough password to sufficiently mitigate most brute force attacks. Even a 16 character password with just mixed case letters has a pretty large search space, assuming your passwords have sufficient entropy.

Having said all that, I’m all for sites supporting longer passwords. Length does allow people to make more complex passwords that are far easier to type, which can be good for people just learning good password hygiene. Also, if it helps people feel more secure to have a longer password and adding support for longer passwords is trivial, why not support it?

Obviously, if there is a massive increase in available computing power anytime soon, some of these assumptions will have to be reexamined. That said, I suspect we’ll have bigger issues to deal with than just the security of our passwords.

Disclaimer: My employer, Check Point Software Technologies, didn’t offer an opinion on this issue. The above thoughts are my own.