Apple wrote a letter to customers regarding a request they had received from the United States Federal Bureau of Investigations to essentially “backdoor” an iPhone in possession so they can retrieved the encrypted data on it. I have reproduced the letter in it’s entirety below for posterity sake.

Data is protected on devices such as the iPhone with math. That’s all cryptography is, folks: math. Granted, it’s well beyond the stuff that most people learn in school, but it’s all math in the end.

Aside from the specific math used in cryptography, what makes cryptography able to protect data is the encryption key, which itself is merely a large number. A fact, if you will. If that fact gets out, you can undo the encryption. This is why Apple and anyone else doing cryptography correctly goes to great lengths to ensure that encryption key is kept private and the math used to encrypt the data is strong enough that they can’t derive the encryption key from the encrypted data.

While it’s possible to create encryption schemes where some third party has (or can derive) the encryption keys, which many governments are now asking for, keep in mind those encryption keys are merely facts. Facts that, once they are out there, can be used by anyone (“good” or “bad”) and cannot easily be changed. These schemes put everyone’s data at risk. (This is also why biometric data used for authentication purposes on it’s own is not so fantastic, it’s merely a fact that cannot be changed, but can be replicated.)

The worst part is the government probably already has all the information they need thanks to all the metadata they collect at the nation’s telecom providers today. Why aren’t they using that, or any number of other traditional methods of investigation, instead of asking Apple (and by extension other device manufacturers) to make their devices less secure?

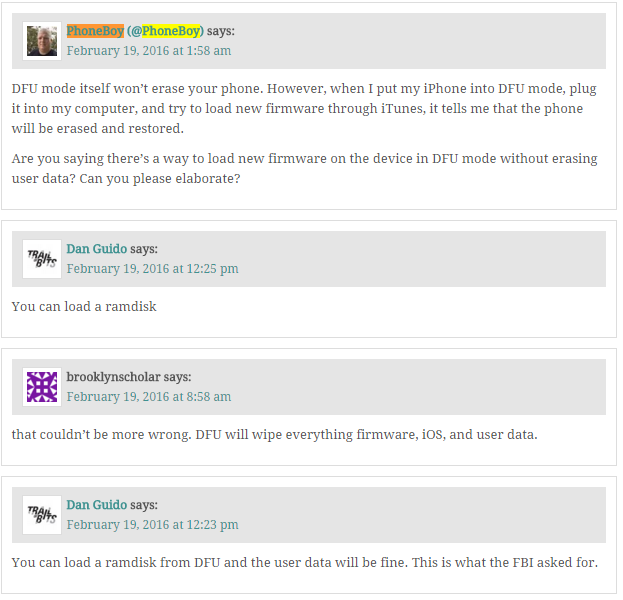

Edit: Yes, I realize the FBI is asking for Apple to disable the 10 passcode tries erases the device option on devices, not backdoor the actual encryption (as noted in this Techdirt article. It’s effectively disabling a key mechanism to protect the encryption keys, which ultimately has the same effect as backdooring the encryption itself.

Disclaimer: I don’t know what my employer Check Point Software Technologies thinks about this. I didn’t ask. These are my own thoughts.

February 16, 2016

A Message to [Apple] Customers

The United States government has demanded that Apple take an unprecedented step which threatens the security of our customers. We oppose this order, which has implications far beyond the legal case at hand.

This moment calls for public discussion, and we want our customers and people around the country to understand what is at stake.

The Need for Encryption

Smartphones, led by iPhone, have become an essential part of our lives. People use them to store an incredible amount of personal information, from our private conversations to our photos, our music, our notes, our calendars and contacts, our financial information and health data, even where we have been and where we are going.

All that information needs to be protected from hackers and criminals who want to access it, steal it, and use it without our knowledge or permission. Customers expect Apple and other technology companies to do everything in our power to protect their personal information, and at Apple we are deeply committed to safeguarding their data.

Compromising the security of our personal information can ultimately put our personal safety at risk. That is why encryption has become so important to all of us.

For many years, we have used encryption to protect our customers’ personal data because we believe it’s the only way to keep their information safe. We have even put that data out of our own reach, because we believe the contents of your iPhone are none of our business.

The San Bernardino Case

We were shocked and outraged by the deadly act of terrorism in San Bernardino last December. We mourn the loss of life and want justice for all those whose lives were affected. The FBI asked us for help in the days following the attack, and we have worked hard to support the government’s efforts to solve this horrible crime. We have no sympathy for terrorists.

When the FBI has requested data that’s in our possession, we have provided it. Apple complies with valid subpoenas and search warrants, as we have in the San Bernardino case. We have also made Apple engineers available to advise the FBI, and we’ve offered our best ideas on a number of investigative options at their disposal.

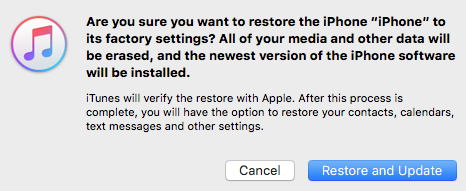

We have great respect for the professionals at the FBI, and we believe their intentions are good. Up to this point, we have done everything that is both within our power and within the law to help them. But now the U.S. government has asked us for something we simply do not have, and something we consider too dangerous to create. They have asked us to build a backdoor to the iPhone.

Specifically, the FBI wants us to make a new version of the iPhone operating system, circumventing several important security features, and install it on an iPhone recovered during the investigation. In the wrong hands, this software — which does not exist today — would have the potential to unlock any iPhone in someone’s physical possession.

The FBI may use different words to describe this tool, but make no mistake: Building a version of iOS that bypasses security in this way would undeniably create a backdoor. And while the government may argue that its use would be limited to this case, there is no way to guarantee such control.

The Threat to Data Security

Some would argue that building a backdoor for just one iPhone is a simple, clean-cut solution. But it ignores both the basics of digital security and the significance of what the government is demanding in this case.

In today’s digital world, the “key” to an encrypted system is a piece of information that unlocks the data, and it is only as secure as the protections around it. Once the information is known, or a way to bypass the code is revealed, the encryption can be defeated by anyone with that knowledge.

The government suggests this tool could only be used once, on one phone. But that’s simply not true. Once created, the technique could be used over and over again, on any number of devices. In the physical world, it would be the equivalent of a master key, capable of opening hundreds of millions of locks — from restaurants and banks to stores and homes. No reasonable person would find that acceptable.

The government is asking Apple to hack our own users and undermine decades of security advancements that protect our customers — including tens of millions of American citizens — from sophisticated hackers and cybercriminals. The same engineers who built strong encryption into the iPhone to protect our users would, ironically, be ordered to weaken those protections and make our users less safe.

We can find no precedent for an American company being forced to expose its customers to a greater risk of attack. For years, cryptologists and national security experts have been warning against weakening encryption. Doing so would hurt only the well-meaning and law-abiding citizens who rely on companies like Apple to protect their data. Criminals and bad actors will still encrypt, using tools that are readily available to them.

A Dangerous Precedent

Rather than asking for legislative action through Congress, the FBI is proposing an unprecedented use of the All Writs Act of 1789 to justify an expansion of its authority.

The government would have us remove security features and add new capabilities to the operating system, allowing a passcode to be input electronically. This would make it easier to unlock an iPhone by “brute force,” trying thousands or millions of combinations with the speed of a modern computer.

The implications of the government’s demands are chilling. If the government can use the All Writs Act to make it easier to unlock your iPhone, it would have the power to reach into anyone’s device to capture their data. The government could extend this breach of privacy and demand that Apple build surveillance software to intercept your messages, access your health records or financial data, track your location, or even access your phone’s microphone or camera without your knowledge.

Opposing this order is not something we take lightly. We feel we must speak up in the face of what we see as an overreach by the U.S. government.

We are challenging the FBI’s demands with the deepest respect for American democracy and a love of our country. We believe it would be in the best interest of everyone to step back and consider the implications.

While we believe the FBI’s intentions are good, it would be wrong for the government to force us to build a backdoor into our products. And ultimately, we fear that this demand would undermine the very freedoms and liberty our government is meant to protect.

Tim Cook